There is a problematic trend, with a lot of goalkeepers focusing on the ball being injected at the short corner, rather than the shot itself. This makes things harder in the save process, for making an effectual successful stop, as you are more focused on the injection, than the shot you have to stop. By being horizontal to the injector and therefore turned away from the incoming shot, you are in fact making things harder for yourself and reducing your chances of making the all important save. Instead, you can improve your success on short corners, by simply learning to focus on the shot; giving yourself more time to prepare for the save.

Being side-on

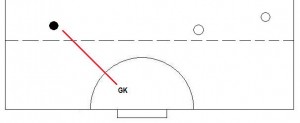

A lot of goalkeepers in Britain, western Europe (Holland, Belgium, Germany, Poland etc.), as well as Asia and Oceania (Australia and New Zealand), like to stand side-on, facing the injector at short corners, in order to watch the injection process and check the ball is properly released (making sure the attempt is not stuffed up by the injector!), before stepping out to face the shooter. Although it is in general use in goalkeepers across different leagues, it is also being used at international level by goalkeepers like Max Weinhold, Tim Jessulat (both of Germany), for example.

The reason behind this technique is that the goalkeeper is able to see the injection, following it through to the shot, tracking the ball and maintaining focus on it, into the save (maintaining eye contact with the ball allowing them to maintain their focus). By turning sideways they also give their defenders more room to move (with the 5 defenders, to defend the corner, standing within the goal). By being able to watch the injection process, they are also able to call out their defence on the time the ball is released, so they have a better chance of setting up in time for the shot/the runners have a better chance of a quick exit. The central focus is therefore on the injection process; completely ignoring the need to stop the shot, which is the more important – the goalkeeper’s fundamental task being keeping the ball out of the net.

This process, however, affects the goalkeeper’s ability to make an eventual save on the short corner attempt; rather than simply stepping out ready to stop the ball, the goalkeeper has to go through a series of before they can get ready for a save. The method itself over complicates the process of stepping out from goal and into position, as you have to turn your body in a swift motion and then step out of goal (slowing down the process of moving out from goal). By turning in this way, you can also end up away from your start position; the centre of goal, when turning round. You are moving yourself away from the destination of the incoming shot, especially if the shot is straight down the middle and around that area.

Focusing your efforts on watching the injector is also detrimental, as you have diverted your attention away from the upcoming shot. With your focus on the person injecting and watching the ball being transferred, rather than the actual shooter, you are not aware of the intended and therefore hampering your chances; you only have a short time to react to it as it happens. You are simply ‘in the dark’, unaware of the routine the opposition are going to use. Having not paid attention to the way the opposition has set up their attack, not knowing what they intend to do, you have no idea what you are facing. By doing so, you drastically limit your chances of making an efficient save; as you change your focus to the shooter, you have little time to react to the shot and therefore have little chance of making the save.

Facing forward

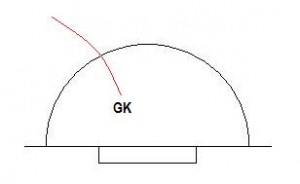

In comparison, a lot of technically sound goalkeepers prefer to stand with their body facing the intended shooter; already ready to deal with the expected shot when they step out from goal. The change in technique comes as a result of goalkeeper specific coaches rethinking the way goalkeepers should behave. The current crop of Dutch super keepers in the Hoofdklasse, use this technique. It is also spreading on the international scene, with goalkeepers like America’s number 1, Tom Sheridan, using the same method.

It is an important method of prioritising for the shot; getting ready before, rather than having to react immediately, once you have stepped out of the goal. At the highest level, the speed of injection is so fast that there is little time to react, complicating things if you were to stand sideways and then have to re-adjust in an instant. When you are faced with such speeds, it is important to try to gain an advantage, even if it is small. By being set already you give yourself that extra millisecond of extra time to react and read the ball better as it comes towards you, which may not have been possible if you had to turn into the shot. With little time to react, focusing on the ball is more useful; your focus is on the shot and you can therefore make a better ‘read’ on it.

In contrast to the side-on method, the complications of turning as you step out from goal are non-existent. Since you are already facing forward and set up centrally, you are already in an optimum position before you have moved out from, or set up for the set. If were are side-on, facing the injector, then you are not going to be able to exit quickly or efficiently; by off setting your position and balance, you slow down (having to reset yourself to position for the shot). Facing forward, however, you are able to set up with increased speed, giving you the time advantage. With your body facing (rather than having your hip tilting out to the side), you can balance and provide forward thrust for when you launch forward out into the D, for extra speed.

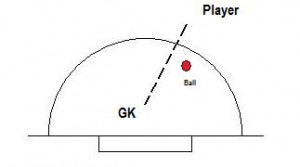

By being set up already facing the shot (rather than parallel to the injector) to start off with, you are in a better position to stop the eventual shot. With a forward view, you can pay attention to the opposition’s set-up around the top of the D. By facing the shooter, you can easily tell whether or strike or flick is coming (by their hand positioning), whilst you can also get a good look at the shape of the opposition’s corner routine (where the ‘castle’ is i.e. where the ball is being stopped and if there are any other dangers, such as deflectors running in).

Face the shot

When you are just about to stop a shot, you are already pre-set in a balanced, stable ready stance and your focus is on the ball – as a result, you can make a successful save. When you are setting up on a short corner, you should therefore be doing the same; setting up in a stance relating to the type of shot you are focusing (well balanced, hands ready according to the anticipated height of the shot/flick), with your eyes focusing on the shooter and then their shot (as they receive the ball and shoot). If you watch the high performing Dutch goalkeepers, such as Klaas Veering, Jaap Stockman, Guus Vogels, and Pirmin Blaak, (who are all coached by Martin Drijver) you will notice that they now all focus solely on the shooter. As do Spanish goalkeepers, like Fransisco Cortes (who is also coached by Drijver). Stockman even goes so far as ignoring calling the defence to move out on the injection (so that the defenders get in the right positions in time), in order to prioritise the save.

The fundamental skill of watching the ball has been lost in the sense of watching the injection; taking it literally, coaches and goalkeepers alike have seen it as essential to focus on where the ball is, with the injector, which is not as important. However, the priority should be on the shooter and focusing on their stick, and following the focus on through; before they receive the ball, then when they take the shot, since that is the where the shot is coming from. By preparing early, rather than just before you have to make a save, your mind is already on the job at hand, whilst you are also physically ready (set in your stance) – reacting better to the flick/shot with increased focus and therefore making the save.

The goalkeeper in this video works as a good basic example of the technique, with them moving straight out from a forward from a forward facing stance, into their ready position to face the shot.

Facing forward on corner

The following video shows the technique in game use:

Vogels in action with the technique

The following is an interesting study by the University of Amsterdam, which proves the theory; with the goalkeeper reacting better when they are focusing on the shot, rather than the injection. Notice how the goalkeeper reacts better when they are watching the shooter. Although they do not make the save, they react much better, anticipating where it is going and able to make a proper ‘read’ because of their focus on the shot.

Study on facing forward, not watching injection

Pointers:

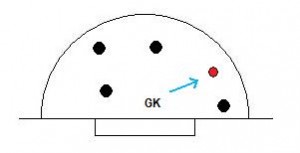

- Align yourself centrally in the goal and facing forward

- Make sure you are facing the shot; start by having your head turned towards the shooter, then make sure your hips are straight, so your whole body is set forwards, to enable an easier transition to your ready stance when you move out

- If you aren’t comfortable standing straight up and feel unbalanced, then you can use your rear leg to support yourself

- Focus on the ball is more important – look to work out the shooter early on

- The quicker you exit the goal, the more time you have to prepare

- Watch the ball from the point the shooter receives the injected ball into the save – start by focusing on the shooter

- Focus mentally on making the save to increase your ability; mental focus helps you focus on the shot and therefore the save

Admittedly the side-on method allows you to watch the injection happen and then call your defenders to move out in time, with your head already positioned to face the injector and see the pass out, BUT it does affect your ability and chances of making the save. If you are intent on getting ready for the save, then you could have a defender (organising this before you set up the corner defence); making sure that they are aware when to call it.

Face forward!

Ultimately, to give yourself the best chance of making the initial save when facing a short corner, you need to be facing forward, so that you face the impending shot. By being pre-set and prepared in advance, you give yourself that extra time to get ready (rather than wasting essential time), as well as extra focus to concentrate on the task at hand, which is crucial to stopping the ball and eliminating the scoring chance that could level the score or put your team a goal down. This way you have more control over events; increasing and improving your chances of making the save by being better prepared.