We get a lot of questions about penalty corners, especially lying down on corners. Laying down, or logging, is only one technique that a keeper can apply in the context of his, or her, team’s penalty corner defence. No one technique, or type of defence, will be successful against every corner attack. This month’s tip focuses on some concepts of penalty corner defence and specifically one technique for logging.

Logging builds on the fact that the first struck shot on goal in a penalty corner must be below 18 inches when it crosses the goal line to be a legal goal. Notice that word “struck,” flicks or deflections do not need to be below 18 inches. Continuing on the struck concept, some people can hit the ball hard, very hard in fact. So hard, that when the shot is taken from fifteen yards at the top of the circle, a keeper doesn’t have time to react. Somebody got to thinking and reasoned that if you can’t react to a hit ball from that distance and it has to be below 18 inches, why not have the keeper lie down and not have to react? In theory this sounds quite simple, but in application it can be quite a different matter.

There are a number of variables that need to be taken into consideration when a team decides how they want to defend corners and whether logging is right for you as a keeper. The equipment you use, the surface you play on, the quality of your opposition’s attack (first shot and options), and the strengths of your defence, all need to be factored in when making a decision.

Equipment is the most important factor in even deciding whether logging is an option for you. In my mind, it’s kind of like deciding whether a parachute is a good option for skydiving. As insane as it sounds, I’ve seen keepers lay down with kickers, leg pads, gloves, helmet, small chest pad, and cotton shorts. In logging, a keeper is using his whole body to take away the bottom of the goal, which means your whole body should be protected. Well padded pants, pelvic protection, upper body pads that cover the arms and chest, as well as a throat protector are all highly recommended in addition to standard kit before a keeper even starts to think about logging.

Next comes playing surface. Logging is primarily a turf skill. Given the somewhat unpredictable nature of grass, it doesn’t make a lot of sense to go down on grass. The 18-inch rule on struck shots only applies to raised shots. If a shot is raised because of the ground/grass, the goal counts. In addition, it’s usually harder to stop the ball dead to set up the shot on grass so defences are usually more effective breaking corners up before the shot.

It’s extremely useful to have an idea of what your opponents are capable of doing on a corner. You need to have a pretty good idea that the other team is capable of scoring off a straight shot with a keeper playing upright before logging. You also need to know what other options an opponent has for their corners. Drag flicks, passing options and deflections all can make the logging keeper look silly.

Finally, logging needs to fit in with how your team is defending corners. If your team is breaking up corners at the top of the circle, there is no straight shot to defend. The keeper needs to be able to react to the broken play and the different gaps that open up as a result and is better served by staying up.

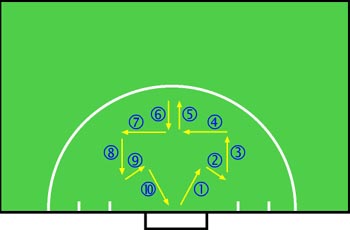

Having said all that, logging can be an effective technique when properly implemented. As we talked about before, logging is based on taking away a scoring area that is effectively 18 inches by four yards. The keeper doesn’t have to do that alone; he should have a post player working with him.

The size of the keeper and the reactions of the post player will determine where the two should best position themselves. Going back to the four yard by 18-inch goal, on hits from penalty corners, the post player is responsible for one yard, the keeper three. The post player is positioned to the keeper’s left facing out from the goal. When the keeper goes down, he’s going down to his right (strong stick side). How far the keeper is off his line will depend on his size, speed and the speed of the push out and stop. Generally, a keeper wants to get to a spot between two to four yards off the goal line.

Movement on a corner is all about efficiency. Extra time spent getting set up is time taken away from being set for the shot. This starts with the goalkeeper’s positioning as the corner is being pushed out. Many keepers turn their body to face the player pushing out. They then turn their body to face the shooter. It is simpler for the keeper to face the shooter from the start and just turn his head to see the push out.

Continuing with efficiency, a keeper needs to know exactly how many steps he needs to get set to go down. He needs to know the angle he needs to be on for where the shot is coming from. He needs to how much space he needs to allow for the other players on the corner defence. This knowledge only comes through repetition with the entire defence involved.

On virtually all corner defences, one player comes out from the left of the keeper between the post player and the keeper. This means the keeper won’t be starting from the middle of the goal when the corner is pushed out. The line the keeper takes out of the goal will depend on where the shot is being taken. With the shot taken from the centre of the circle, the keeper will step out lining his right leg up at the centre of the goal if he’s logging. This typically means that he’s stepping out to his left as he goes towards the shooter. If a keeper centres his body on the shot and the goal instead of his right leg he’ll end up covering from the middle of the goal to the right when he lays out, leaving his post player the whole left side of the goal. Once again, you’ll need to work out where you need to go down from through repetition with your post player as you figure out how to most effectively cover the goal.

A couple of things about post players: first and foremost, they are a goalkeeper’s best friends. When a keeper logs on corners, he’s counting on the post player to cover his back. Be consistent and clear with each of your responsibilities and expectations. Once again, this comes through repetition in practice. Penalty corner practice can be dangerous. A post player has to be fearless. There is no blame in short corner defence. There are mistakes, but no one points the finger. Like a keeper, the post player’s positioning on corners will depend on his speed coming off the line, getting set and reaction time. A post player needs to play where he will make saves.

Remembering that he’s responsible for saving shots at an area of the goal one-yard by 18 inches; the post player’s job starts there. I’ll leave specifics of post player technique to the experts, but generally the post player wants to step up even with the keeper as the keeper is set to go down. If the post player sets up behind the keeper he’s vulnerable to deflections off the keeper, deflections by attackers in front of him and will have a long way to go if he’s to help clear rebounds off the keeper’s pads. Helping clear rebounds off the logging keeper’s lower body is an essential part of his responsibilities. A post player makes his job easy by knowing where his goal is and this starts with positioning and playing shots on his front stick. As he steps out, he wants to line his left leg up on the left post. By doing this, shots outside his left leg should be wide of the goal (I won’t guarantee for irregularities in pitches). This is only a start for the post player, depending on the style of defence your team plays and the variations your team encounters the job changes.

Finally we get to logging. There are two primary techniques for laying down on corners. The first starts from a leaning position, the second from a kneeling one. Other people may have different names for the techniques, but for our purposes we’ll simply call them the lean and the kneel (we’ll deal with the kneel and other logging techniques in our next tip).

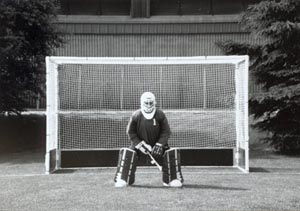

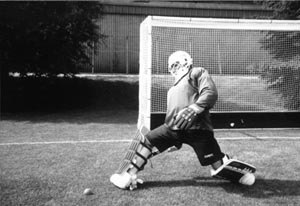

In the lean technique, a keeper is looking to be set in a leaning position ready to drop when the ball is struck. To recap, his movement will be slightly diagonal left to account for the player coming out from his left as he centres himself on the shot. The distance he comes off his line will depend on his size and speed coming off his line. His set position will be in a crouching lean, with his left shoulder above his right foot. His left hand is at his chest and right hand is down and stick held out to the side.

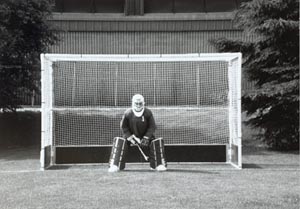

The keeper set up in the lean position, stick out, left hand in front of the chest, left shoulder over right foot. Note the position of the right leg at the middle of the goal.

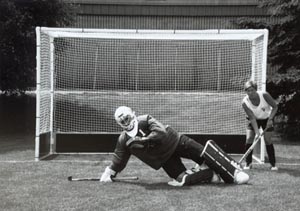

As the ball is about to be struck, the keeper collapses his right leg straight out (towards the left post), looking to get his right hip down. At the same time the keeper extends his stick out for maximum width and height. Fully extended means being able to cover the height of the backboards. When laid out, your left hand should cover the right side above your stick. Your stick should cover an area slightly wide of the goal.

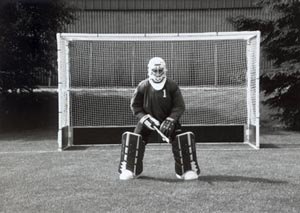

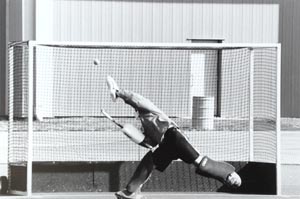

Going down on the hit, the keeper collapses the right leg. As the hip comes down and the right leg straightens, the keeper’s body extends to the left.

When a keeper is laid out, make sure your body is vertically angled forward with your left hip and shoulder slightly in front of your right as you’re down. Many keepers set up in the lean with their right foot slightly behind their left to ensure that their body won’t be angled back as they go down. The last thing you want to be is a human ramp, deflecting the ball into the goal. The same applies to your stick. Make sure the toe of your stick is slightly forward so the shot doesn’t deflect in. That may mean adjusting your grip as you set up for corners.

Once down and extended out, the keeper and post player effectively cover the bottom part of the goal.

Some keepers almost brace themselves with their stick in the lean position. This helps them get down more smoothly. You want to get your right hip and arm down and out as quickly as possible when dropping for the hit. By bracing yourself with the stick, you ease your drop as you go down. It’s important not to get stuck on your right elbow. If you do, there will be a gap under your armpit. A keeper doesn’t want to flop. Flopping usually happens when a keeper doesn’t collapse his right leg, but pushes off of it as he goes down. If he does this, he ends up going up before he goes down. He’ll have a hard time getting his legs extended and is usually still coming down when the shot is coming to goal.

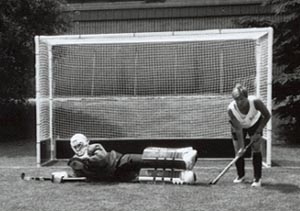

Now that he’s down, how does the keeper make a save in the logging position? Saving shots below the waist in a prone position is a fairly straightforward proposition for the keeper. Basically he is just letting the ball hit him. As we mentioned before, the keeper must have his left (top) hip slightly of his right (bottom) or the shot will deflect off of him, up and into the goal. The keeper needs to be consistent with what he does with his feet while down. If the keeper is pointing his toes down for extra length, he needs to do that all the time, otherwise he creates confusion (and deflections) for the post player. In almost all defences where a keeper is down, the post player is responsible for clearing saves off of the keeper’s lower body.

Shots above the prone keeper’s waist present a different set of issues. As the keeper is down waiting for the shot at goal, he wants to keep his left hand at his chest. If the shot is between his waist and chest, the keeper wants to keep the ball as close to his body as possible. The easiest way to do that is to trap the shot, almost patting the ball palm down with his left hand. Depending on the defence a team plays, the keeper may be responsible for clearing these shots. If clearing for himself, the keeper is using his stick, taking his left hand off the ball and sweeping the ball to his left with his stick. If a keeper is clearing for himself, he needs to call it, otherwise he risks hitting the post player with his clear, or just as bad, the two going for the same ball.

As for shots that are above the keeper’s chest in a prone position, much will depend on the height of the shot. Shots on the ground are easier as they can be saved with the stick. The important thing with stick saves is the angle of your stick. Not only is it important that your stick isn’t angled toe back, angling your stick back towards the end line can be most beneficial. You don’t want to deflect the shot into the goal, but if you can put it out of play you’re looking at a long hit, not a fat, juicy rebound.

Taken from an angle, this photo illustrates angling the stick back to save the shot over the endline.

Two areas present a problem: the area under the keeper’s right arm and balls above the stick. Don’t think that because you’re stretched out with your side flat, a ball hit at your right armpit will stop when it hits you. Unless you can dislocate your right arm, there’s always going to be a gap there when you go down. The other bit of nastiness is that there is no padding under your arm. Use your left hand to cover the gap. You also want to use your left hand to make saves above your stick. Just as you want to angle your stick back when making save on the ground to that side, you make your job easier by angling your palm towards the side/end line when making a save with your left hand. Once again, there is a bonus to setting up with your right foot slightly behind your left when setting up in the lean, your body is already angled back towards the end line when you’re stretched out for the save. A keeper is going to need help with rebounds off shots above his chest when he’s down. Many defences keep a player low off to the keeper’s right specifically for that reason. Like rebounds off the keeper’s lower body, there has to be a clear understanding of who is clearing rebounds off the keeper’s hands. In penalty corner defence, confusion equals goals.

We’ve talked about a lot of concepts and mechanics within the skill in this tip. All of them need to be mastered if logging is going to be effective. Footwork needs to be practiced. Set up, positioning, the lean, getting down, the save and clear all need to be done in synch before you can expect to successfully log in games. As mentioned before, success comes with repetition. Make sure your penalty corner defence practice allows you an environment to learn and master the technique.

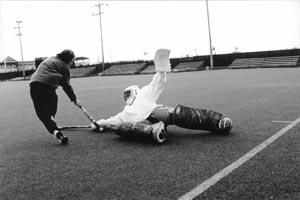

Practicing logging. Going down on the strike.

Good luck,

Jon

e-mail Jon

Please note that OBO together with Jon O’Haire hold copyright over any material appearing on tips pages. We welcome the printing and distribution of these tips, provided that they are not sold, or used for financial gain. This paragraph must appear on all printed or distributed copies. The photographs above must not be used in any form without express permission from Jon O’Haire.